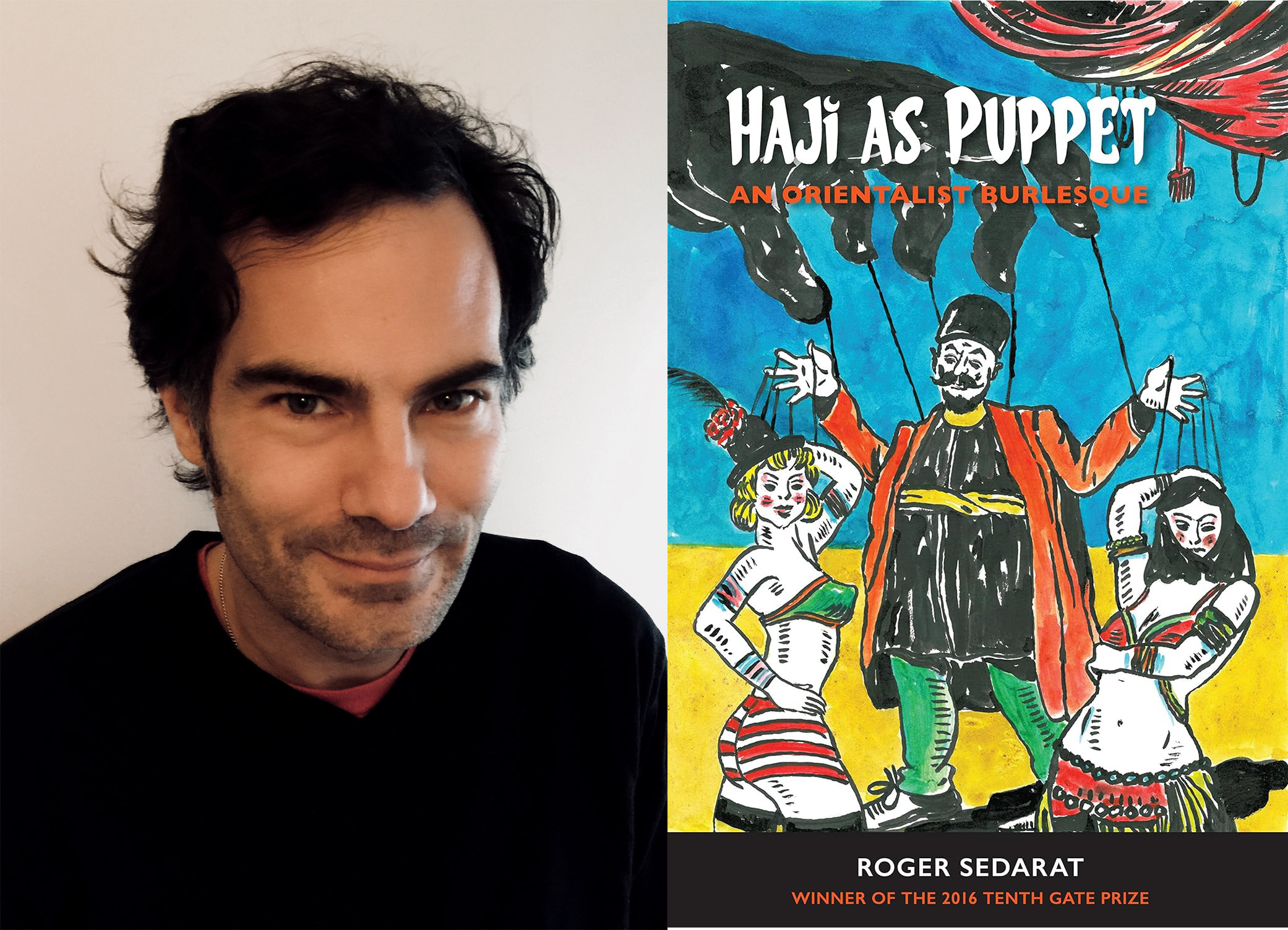

Wine swirling into a glass, the crackle of the freezer icebox churning, a cube of ice plopping into the red wine (serve chilled, the lukewarm wine bottle reads): I inaugurate this article by sprinkling sweet wine onto Roger Sedarat’s most recent poetry book Haji as Puppet: An Orientalist Burlesque.

In honor of National Poetry Month, an interview with a local poet was called for. The recipient of many awards, such as the 2016 Tenth Gate Prize for Mid-Career Poets, and credited as a pioneer in Iranian-American poetry — I could think of no one better to interview than Queens College’s very own Roger Sedarat, a professor in the English department.

Sedarat and I sat down together at a distance, a Zoom call uniting us on a day neither of us could make it to campus. Our conversation flowed like fine wine, a metaphor that permeated the depths of our conversation, from the wine spilled on Walt Whitman’s book to the divine intoxication of Persian poetry.

Over the course of the conversation, a real concern came up: That Islam isn’t spoken of enough in American culture.

“There’s a genuine concern, and I think that obviously the situation with Gaza subsumes everything,” Sedarat said. “I was thinking about writing an Op-Ed to the Times or something about, like, why aren’t we — or can we actually talk about Islam?”

This question, along with his elementary school love of Shel Silverstein, has compelled Sederat to write for quite some time.

“It really did all start with being a little kid, picking up the phone and people in Texas anonymously telling me — as a little kid! — that I had to tell my dad we had 24 hours to move, they were gonna burn our house to the ground. Getting beaten up, getting our windows broken,” Sedarat said. “My dad was telling me, ‘Tell everybody we’re Greek,’ and I was like, ‘Why can’t I – why couldn’t I tell people?’”

Now he tells the world, and unapologetically so, as both poet and professor.

Sedarat has worked to educate students on the diversity of Middle Eastern cultures and their complexity. Shortly after 9/11, for example, he designed a course in Middle Eastern Literature in Translation at Borough of Manhattan Community College:

“I guess I did it because there was so much misunderstanding. In New York City there was outrage that they were building a school, calling it the Kahlil Gibran High School,” Sedarat said. “It was close to 9/11. But Kahlil Gibran is Christian! People don’t even understand today.”

Talking about difficult topics isn’t foreign to Sedarat, something his students appreciate him for. One student, Jasmine Hsu, a Senior majoring in English, was impressed by Sedarat’s ability to compassionately tackle difficult cultural topics:

“He knew how to make the topics fun to discuss,” Hsu said. “He was very open with people’s responses, and to really challenge certain ideas and to really think about why people are the way they are.”

Isabella Puentes, another Senior majoring in English, specifically chose her Senior Seminar class because it was taught by Professor Sedarat:

“I just thought of how complicated a Senior Seminar actually is,” Puentes said, “and I just really wanted his intro and his perspective on how to handle more advanced and critical English theory.”

Professor Sedarat and I returned to the intersection of cultures in the Middle East, the birthplace of Judaism, Islam , and Christianity, many times during the course of our conversation.

“In a post-colonial course I taught – where we were talking about what colonialism is, and the problems, and different cultures – we had Orthodox Jewish students next to pretty conservative Muslim students and we were actually having conversations,” Sedarat said. “You’d never believe it, you’d never believe that could happen. There was actually a lot of understanding.”

In his studies, Sedarat has discovered a distinct connection between Persian and American poetry. One such example is this Arab-Persian poetry book, which greatly influenced Walt Whitman’s war-time book Drum Taps.

“So many of these civil war poems he’s writing,” Sedarat said, “He’s imitating Persian and Arab poetry, and I’m like — and nobody knows this!””

With war once again tearing apart the Middle East, it’s more important than ever to have conversations about the Middle East — about how it has influenced American culture, about how its diverse cultures have historically mingled, and about what it means to be Muslim in America.

“[Because of the Israel-Palestine conflict] there’s a different kind of traumatic reawakening to all of these things that have always been with us — with everybody, by the way — my Jewish friends as well,” Sedarat said.

And, like the Persian poetry that helped Whitman in the midst of the grief of war, perhaps poetry can help bridge the gap in our time as well:

“One-for-one, it’s like people communicating the deep loss, the deep anger, all of these emotions, in a different form, in lyric expression as opposed to just lamenting or just arguing. It’s a different way of communicating,” Sedarat said.

America has historically been full of “others” who seem monstrous in their muteness. Today, one of these groups are Middle-Eastern Americans. Let’s drink the wine of communion together. Let’s give voices to the silent. Let’s make poetry.