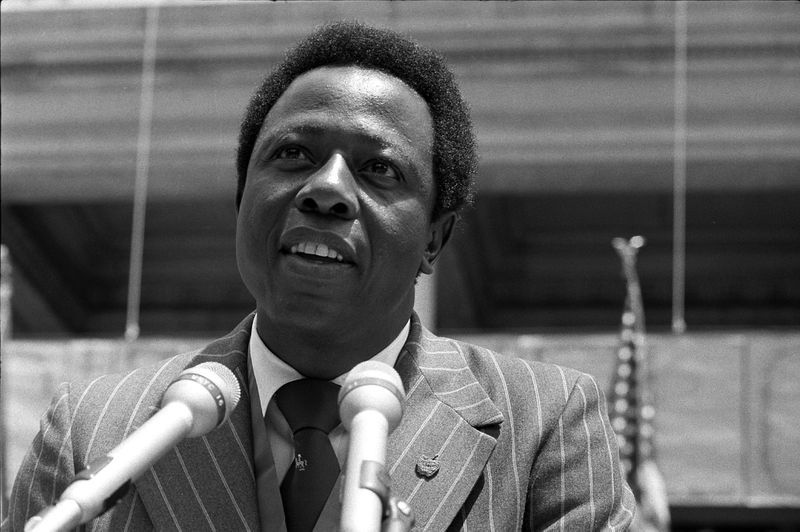

Late last month, the sport of baseball lost one of its titans. Hank Aaron, the man who defined excellence in baseball for two decades while playing under the burden of racism, died at the age of 86.

Aaron’s fame transcended his sport. During his pursuit of the home run record, school children would dash home and check the daily papers to see if “Hammerin’ Hank” hit another one. Every bit of his fame was well-earned and would have had his career taken place in a vacuum. Aaron hit 755 home runs, the most of any player who was never suspected of steroid use, and his 2297 runs batted in and 6856 total bases, according to Baseball Reference, are the most in baseball history.

Hank Aaron’s career didn’t occur in a vacuum, though; it has to be considered in the context of the era in which he played. Major League Baseball had only accepted black players into its ranks for seven years when Hank Aaron made his debut in 1954. He had previously played for the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League and often recounted a story in which the team, after having eaten at a restaurant, could hear the owners destroying the plates off which they had eaten, preferring to destroy plates which black men had used than re-use them. He would later state, “If dogs had eaten off those plates, they’d have washed them.”

And that was before he became one of the most premiere players in the sport, and, along with Willie Mays and Stan Musial, its most spotless representative. Even when dogged with death threats and racist hate mail for the cardinal sin of playing a game, Hank Aaron was unbowed. Ralph Carhart, theater professor at Queens College and baseball historian, discredits “the belief that [Hank Aaron] endured the racism he faced without anger or resentment…it’s hogwash. Aaron did not accept the vitriol complacently at any point in his career, even after his playing days. He became a fierce advocate for Black players and was a powerful voice in pushing MLB to open up its management ranks to non-whites.” Nevertheless, the sting of racial hatred stuck with Aaron long after his playing days were over. NPR quotes Aaron saying, “The bigger difference is that back then, they [racists] had hoods. Now they have neckties and starched shirts.” Aaron rose above the venom of his day employing the same tenacity with which he approached every at-bat. His desire to advance the greater good persisted to his last days; he was one of the first high-profile celebrities to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in January, helping to put skeptics at ease.

“Hammerin’ Hank,” in a very important sense, helped to make the game truly American, especially in tandem with fellow baseball immortal Willie Mays. Reflecting on their relationship, Prof. Carhart acknowledged that, “They inspired each other. If one of them did well, the other was motivated to do better. But it wasn’t a vindictive competition. It was two men who had faced similar injustices and obstacles and who, almost concurrently, redefined the record books.” Hank Aaron’s legacy is that of a man who legitimized the presence of the Black ballplayer in Major League Baseball when he should never have had to in the first place. In opening the gates of America’s pastime to Americans of every color, Hank Aaron has done more than almost anyone else to make the game truly American.